A 10-month-old Massachusetts girl can hear for the first time after receiving cochlear implant surgery in January.

Erin Sinclair and Tyler Sinclair's daughter Charlie was captured on camera reacting to hearing sounds during an audiologist visit at UMass Memorial Medical Center in Worcester, Massachusetts, on Jan. 29, two weeks after she received the implants, electronic devices that were implanted in her cochlea, the hollow and spiral tube in the inner ear.

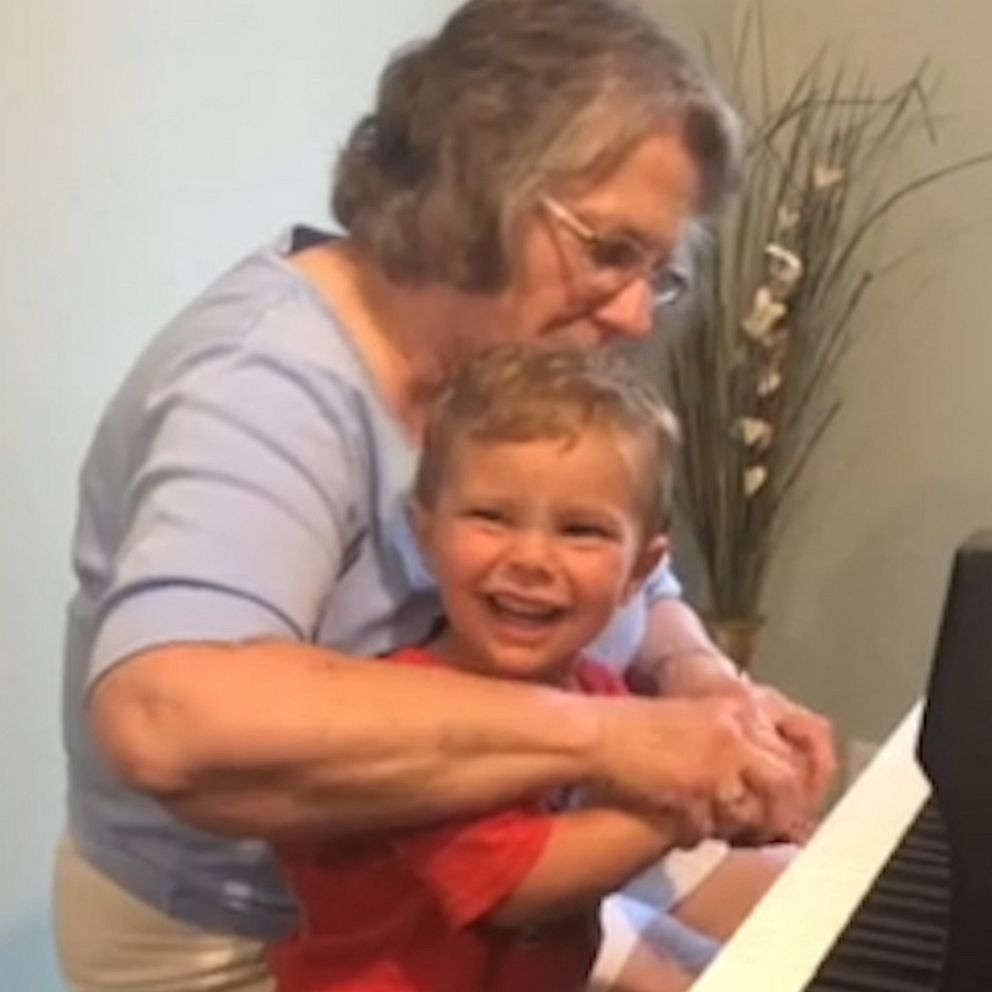

In video clips shared with ABC News by UMass Memorial Health, Charlie is seen seated on her mom's lap and lights up and turns toward her dad when she hears him rattle a sound book and talk to her.

An external microphone, speech processor and transmitter is attached to Charlie's head by her ear, and as the audiologist activates the device, the electrodes implanted in the cochlea help Charlie recognize sounds.

"The activation session was very emotional," Erin Sinclair recalled to "Good Morning America." "It's kind of exciting and overwhelming all at the same time, because you're not really sure what to expect, because they start out at a low level and they keep upping the volume until they respond, and then they back it down a little bit so that it's more comfortable for them. But the whole process itself was very involved and it was very emotional."

Dr. Divya Chari, an ear surgeon at UMass Memorial Medical Center, said in a statement, "For children like Charlie who are born profoundly deaf, cochlear implants are nothing short of life-changing. Early access to sound through this technology provides Charlie with the ability to develop communication and language skills on par with her peers."

The Sinclairs said they didn't realize their daughter was born deaf until a few months after her birth. They said they were surprised when Charlie was first diagnosed with profound or severe deafness, and then later received another diagnosis of a rare condition called Usher syndrome Type 1B.

According to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, Usher syndrome affects 0.004% to 0.017% of the population, or about 4 to 17 per 100,000 people. There are three types -- Types 1, 2, and 3 -- and the syndrome can lead to profound hearing loss, deafness, vision loss and balance issues. Usher syndrome is typically passed down through parents' genes or can be caused by altered or mutated genes.

In addition to learning to hear and listen to sounds, the Sinclairs said they are also learning and teaching American Sign Language to Charlie, so she can have the option to communicate in multiple ways as she grows up.

"ASL is a really important form of communication, even for hearing families," said Erin Sinclair. "That way, she has the ability to communicate, even when she doesn't feel like wearing her cochlear implants."

"If we get older and she wants to just talk with ASL, then that's her choice," Tyler Sinclair added. "You gotta think about her more than you have to think about yourself and think about what she is going to want for herself in the future."